The digitalization of reality, in its race toward incorporating more and more of human life, is well advanced in the area of the media, probably because the media are already a mental construction, a half-way between a direct approach to reality and a mental interpretation.

The media had their physical counterparts and supports which, in time, became less and less “embodied.” Music production – and especially music reproduction, for instance – went from heavy equipment to small MP3 readers. Now we have virtually no physical equipment any more for music, nor for movies and, books themselves are going digital, being contained in small memory chips.

Damasio demonstrated that the brain can’t be understood without the body and the emotions which inform thought and decisions. Analogously, a piece of information without a physical support misses something. As with thoughts, we can’t really detach the media from their physical counterparts. Our relationship with music, for instance, is a multi-sensorial one, being not only auditory, but tactile and visual as well. Beside that, music is a social experience too. And we should not forget that we can feel an attachment to the physical support of music (in the form of LPs or, less, CDs) and paper books or magazines.

The New York Times recently published an article, “Serendipity, Lost in the Digital Deluge”, saying, “there is just too much information. We can have thousands of people sending us suggestions each day – some useful, some not. We have to read them, sort them and act upon them.”

I wrote in “Does the Internet Really Broaden Minds?” how the variety of sources available on the Net bring traffic only to a very restricted set of websites instead of broadening the scope of our search. The same applies to references to scientific papers and music where just 0.4 percent of tracks account for 80 percent of downloads. Researchers have found that when people are more connected to each other on the Net, they tend to concentrate on an even smaller number of sources.

[/en][it]

La digitalizzazione della realtà, nella sua corsa ad incorporare sempre più aspetti dell’umano, è particolarmente avanzata nell’area dei media, probabilmente perché questi sono già una costruzione mentale, una via di mezzo tra un contatto diretto con la realtà e un’interpretazione mentale.

I media hanno avuto i loro equivalenti fisici e i loro supporti i quali, nel tempo, sono diventati sempre meno “incarnati”. La produzione musicale, ad esempio, e in particolare la riproduzione della musica, è passata da pesanti attrezzature a minuscoli lettori MP3. Ora praticamente non abbiamo quasi più alcun supporto fisico per la musica, per i film e anche i libri stanno andando verso il digitale.

Damasio ha dimostrato che il cervello non può essere compreso senza il corpo e le emozioni che informano i pensieri e le decisioni. Analogamente, un frammento informativo senza un supporto fisico manca di qualcosa. Come per il pensiiero, non possiamo veramente separare i media dalle loro corrispondenze fisiche. La nostra relazione con la musica, ad esempio, è multi-sensoriale, non solamente uditiva, ma anche tattile e visiva. A parte ciò, la musica è un’esperienza sociale. E non va dimenticato che possiamo sviluppare un attaccamento anche per il supporto fisico della musica (nella forma di LP o, in misura minore, di CD), dei libri e delle riviste.

Recentemente, il New York Times ha pubblicato l’articolo “Serendipity, Lost in the Digital Deluge” (La serendipità persa nell’inondazione digitale), scrivendo “c’è troppa informazione. Possiamo avere migliaia di persone che ogni giorno ci mandano dei suggerimenti, alcuni utili, altri no. Dobbiamo leggerli, selezionarli, smistarli e agire su di essi”.

Nell’articolo “Internet ci porta all’apertura mentale?” ho scritto di come la varietà di fonti disponibili nella Rete porta traffico solamente ad un insieme molto ristretto di siti web, invece di espandere la portata della nostra ricerca. Lo stesso fenomeno si applica alle citazioni verso gli articoli scientifici e alla musica, dove solamente lo 0,4 percento dei brani rappresenta l’80 percento dei download. I ricercatori hanno scoperto che quando le persone sono più connesse tra di loro in Rete, tendono a concentrarsi su un numero di fonti ancora più ristretto.

[/it]

[en]

The New York Times article also says, “Many software developers are trying to recreate serendipity,” citing websites like Stumbleupon which direct people to random sites according to their preferences. There are similar services for music as well.

Coming back to the physical supports for music, now we can have several thousands of music tracks in a tiny iPod, and can easily get many more. Our time to decide whether we like a piece of music becomes shorter. The era when we listened to a complete LP has gone, and probably most people don’t even dare to listen to a complete song to judge it.

The digital trend is toward no more narrative, toward tiny bits of information, mostly disconncted from each other so a complete album in its broad vision is rarely listened to – much less listened to many times – before we decide whether we like it or not.

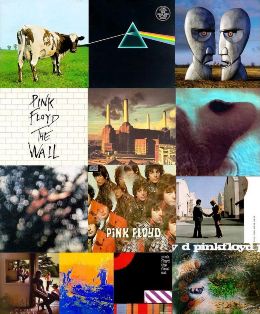

My first contact with Pink Floyd was by a stall of used items at the Fiera di Sinigallia in Milan when I was 12 or 13 years. This man sold copied musical cassette and I bought “Atom heart Mother”. I knew very little about Pink Floyd’s music. It was around 1974 and the few media we had were mostly state radio and TV. The first independent FM radios were just starting. I heard something about those Pink Floyd through older siblings of my peers. Since those people conveyed something about themselves through a direct human contact, I wanted to give a try to that music.

Back at home I put the cassette in my player and didn’t really like it: strange music, tracks as long as 20 minutes. I put it aside. But since I didn’t have that many albums to hear, after a while I heard it again. After hearing it a few times, I think weeks later, there came a revelation. I finally grasped their boundless, deep, sometimes disqueting music, as a narrative of the complete album. Pink Floyd’s music, especially those albums before “The Wall,” is not quick to be grasped, far from being catchy jingles.

Had I approached that album in a ‘digital’ way I wonder if I would have had the patience to hear it till its end and even hear it once more since it didn’t tickle “my taste,” which actually was the musical taste I was conditioned to hear. Good things take time to reveal themselves: they need to pierce through our mental structures and conditionings which automatically tend to reject what’s not familiar. If I would have got it in an iPod maybe I would have skipped the tracks after a few beats, looking for something which would better appeal to my tastes or just I could not concentrate on a full album, being interrupted by SMS, email, chat or whatever online event.

The same mechanism applies even more to the Internet where the short time we have to make a decision to click or not and the information overload don’t encourage time for reflection and, therefore, we tend to fall for what is already known and accepted.

[/en][it]

Inoltre, l’articolo del New York Times afferma che “Molti sviluppatori software tentano di creare la serendipità”, citando a proposito siti come Stumbleupon che dirigono le persone verso siti casuali in accordo alle loro preferenze. Ci sono servizi simili anche per la musica.

Ritornando ai supporti fisici per la musica, ora possiamo avere migliaia di brani in un piccolo iPod, e possiamo facilmente ottenerne molti altri. Il tempo per decidere se un brano ci piaccia o meno è diventato più corto. L’epoca in cui ascoltavamo un completo LP è finita e probabilmente la maggior parte delle persone non osa neanche ascoltare un intero brano per giudicarlo.

La tendenza del digitale è verso la fine della narrativa, verso piccolo frammenti informativi, più che altro disconnessi gli uni dagli altri in modo che un album completo nella sua ampia visione viene ascoltato raramente, ancor meno ascoltato più volte, prima che decidiamo se ci piace o meno.

Il mio primo contatto con i Pink Floyd è avvenuto in una bancarella di cassette musicali piratate alla Fiera si Sinigallia di Milano quando avevo 12 o 13 anni. Sapevo ben poco riguardo alla loro musica, acquistai “Atom Heart Mother”. Era circa il 1974 e le radio e TV di stato erano quasi le uniche fonti in informazione esistenti. Le prime radio indipendenti in FM stavano appena iniziando. Avevo sentito qualcosa a riguardo di questi Pink Floyd da fratelli maggiori dei miei amici. Poiché tali persone mi avevano trasmesso qualcosa rispetto alla loro personalità tramite un contatto umano diretto, ho voluto provare tale musica.

Arrivato a casa, ho messo la cassetta nel riproduttore e non mi era piaciuta tanto: musica strana, con brani lunghi fino a 20 minuti. La misi da parte. Ma poiché non avevo molti album musicali da ascoltare, dopo un po’ l’ho ascoltata di nuovo. Dopo averla ascoltata alcune volte, credo alcune settimane dopo, giunse una rivelazione. Finalmente avevo afferrato la loro musica senza confini, profonda e a volte inquietante. La musica dei Pink Floyd, in particolare per gli album prima di “The Wall”, non è immediata da cogliere, lontana dai motivetti orecchiabili.

Se mi fossi avvicinato a quell’album in modo “digitale”, mi chiedo se avessi avuto la pazienza di ascoltarlo fino alla fine e, ancor più, di ascoltarlo più volte dopo che non si era adattato ai “miei” gusti musicali la prima volta, che in realtà erano i gusti a cui ero stato condizionato nell’ascolto. Le cose di valore richiedono un certo tempo per rivelarsi a noi: necessitano di penetrare attraverso le nostre strutture mentali e i nostri condizionamenti che tendono automaticamente a rifiutare ciò che non è familiare. Se avessi avuto la stessa musica in un iPod forse avrei saltato i brani dopo poche battute, alla ricerca di qualcosa che fosse stato di maggior interesse per i miei gusti, oppure, semplicemente non mi sarei potuto concentrare su un intero album, essendo interrotto da SMS, email, chat o da qualsiasi altro evento online.

Lo stesso meccanismo si applica anche maggiormente a Internet dove il breve tempo che abbiamo per prendere una decisione se cliccare o meno, accoppiata al sovraccarico di informazioni, non incoraggia il tempo per la riflessione e di conseguenza ricadiamo su ciò che è già noto ed accettato.

[/it]