[en]

[en]

The digitalization of reality, in its race toward incorporating more and more of human life, is well advanced in the area of the media, probably because the media are already a mental construction, a half-way between a direct approach to reality and a mental interpretation.

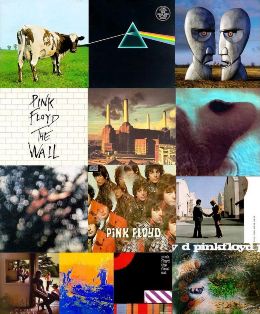

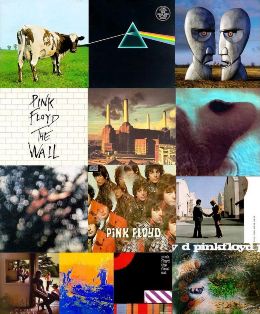

The media had their physical counterparts and supports which, in time, became less and less “embodied.” Music production – and especially music reproduction, for instance – went from heavy equipment to small MP3 readers. Now we have virtually no physical equipment any more for music, nor for movies and, books themselves are going digital, being contained in small memory chips.

Damasio demonstrated that the brain can’t be understood without the body and the emotions which inform thought and decisions. Analogously, a piece of information without a physical support misses something. As with thoughts, we can’t really detach the media from their physical counterparts. Our relationship with music, for instance, is a multi-sensorial one, being not only auditory, but tactile and visual as well. Beside that, music is a social experience too. And we should not forget that we can feel an attachment to the physical support of music (in the form of LPs or, less, CDs) and paper books or magazines.

The New York Times recently published an article, “Serendipity, Lost in the Digital Deluge”, saying, “there is just too much information. We can have thousands of people sending us suggestions each day – some useful, some not. We have to read them, sort them and act upon them.”

I wrote in “Does the Internet Really Broaden Minds?” how the variety of sources available on the Net bring traffic only to a very restricted set of websites instead of broadening the scope of our search. The same applies to references to scientific papers and music where just 0.4 percent of tracks account for 80 percent of downloads. Researchers have found that when people are more connected to each other on the Net, they tend to concentrate on an even smaller number of sources.

[/en][it]

La digitalizzazione della realtà, nella sua corsa ad incorporare sempre più aspetti dell’umano, è particolarmente avanzata nell’area dei media, probabilmente perché questi sono già una costruzione mentale, una via di mezzo tra un contatto diretto con la realtà e un’interpretazione mentale.

I media hanno avuto i loro equivalenti fisici e i loro supporti i quali, nel tempo, sono diventati sempre meno “incarnati”. La produzione musicale, ad esempio, e in particolare la riproduzione della musica, è passata da pesanti attrezzature a minuscoli lettori MP3. Ora praticamente non abbiamo quasi più alcun supporto fisico per la musica, per i film e anche i libri stanno andando verso il digitale.

Damasio ha dimostrato che il cervello non può essere compreso senza il corpo e le emozioni che informano i pensieri e le decisioni. Analogamente, un frammento informativo senza un supporto fisico manca di qualcosa. Come per il pensiiero, non possiamo veramente separare i media dalle loro corrispondenze fisiche. La nostra relazione con la musica, ad esempio, è multi-sensoriale, non solamente uditiva, ma anche tattile e visiva. A parte ciò, la musica è un’esperienza sociale. E non va dimenticato che possiamo sviluppare un attaccamento anche per il supporto fisico della musica (nella forma di LP o, in misura minore, di CD), dei libri e delle riviste.

Recentemente, il New York Times ha pubblicato l’articolo “Serendipity, Lost in the Digital Deluge” (La serendipità persa nell’inondazione digitale), scrivendo “c’è troppa informazione. Possiamo avere migliaia di persone che ogni giorno ci mandano dei suggerimenti, alcuni utili, altri no. Dobbiamo leggerli, selezionarli, smistarli e agire su di essi”.

Nell’articolo “Internet ci porta all’apertura mentale?” ho scritto di come la varietà di fonti disponibili nella Rete porta traffico solamente ad un insieme molto ristretto di siti web, invece di espandere la portata della nostra ricerca. Lo stesso fenomeno si applica alle citazioni verso gli articoli scientifici e alla musica, dove solamente lo 0,4 percento dei brani rappresenta l’80 percento dei download. I ricercatori hanno scoperto che quando le persone sono più connesse tra di loro in Rete, tendono a concentrarsi su un numero di fonti ancora più ristretto.

[/it]

Leggi tutto “Maybe I would Not Appreciate Pink Floyd’s Music if it was Digital”