Ever since the Internet came into our lives it has been regarded as the medium supposed to stimulate a positive meeting between cultures and to ease the spread of information neglected by the traditional media. While it is true that everybody can set up a blog or a website with a small technical and financial investment and share their writings, music or videos for the whole world, it seems that the big media are even bigger on the Net and that the understanding between cultures didn’t improve much even 15 years after the mass diffusion of the Internet.

Ever since the Internet came into our lives it has been regarded as the medium supposed to stimulate a positive meeting between cultures and to ease the spread of information neglected by the traditional media. While it is true that everybody can set up a blog or a website with a small technical and financial investment and share their writings, music or videos for the whole world, it seems that the big media are even bigger on the Net and that the understanding between cultures didn’t improve much even 15 years after the mass diffusion of the Internet.

If we look at the academic level, the Economist published an article titled “Great minds think (too much) alike” where research by James Evans, a sociologist at the University of Chicago, is introduced, whose work has been published in Science. The conclusion of his work says that, “as more journals become available online, fewer articles are being cited in the reference lists of the research papers published within them. Moreover, those articles that do get a mention tend to have been recently published themselves. Far from growing longer, the long tail is being docked.” The long tail is a term coined by Chris Anderson in 2004 to define the niche markets which the Web can approach, where unique products take an important commercial value.

Evans discovered instead that the great variety of papers available on the Net, far from widening the range of quoted sources, actually gave privilege to the ones already well known and even more to the most recent ones, probably the easiest to find searching in Google.

On the commercial level, New Scientist published the article “Online shopping and the Harry Potter effect” writing that “big sellers have never been bigger… Andrew Bud from the cellphone software company mBlox have analysed a year’s worth of downloads from a well-known internet music store. They found that of the 13 million tracks available, 52,000 – just 0.4 per cent – accounted for 80 per cent of downloads”.

New Scientist explains the phenomenon as, “easy digital replication and efficient communication through cellphones, email and social networking sites encourage fast-moving, fast-changing fads. The result is a homogenisation of tastes that boosts the chances of popular things becoming blockbusters, making the already successful even more successful.”

This has been confirmed experimentally by Duncan Watts, a sociologist at Columbia University, New York.

Together with his colleagues Matthew Salganik and Peter Dodds, he tested the effect of communication and peer approval on the musical tastes of 14,000 teenage volunteers recruited online (Science, vol. 311, p. 854;). A set of 48 songs was made available to all the volunteers, who could download whichever songs they wanted. The researchers split the volunteers into eight groups; in some, group members could see what their peers were downloading, but in others they had no such knowledge. In the socially connected groups, the winner took all: popular songs became more popular, unpopular songs more unpopular. This effect was much less pronounced in the socially isolated groups.

Watts thinks that information overload makes us more dependent on other people’s opinions to find out what we like. Then New Scientist asks, “why, when we have so much information at our fingertips, are we so concerned with what our peers like? Don’t we trust our own judgement?”

In another article, a psychologist finds Wikipedians grumpy and close-minded. In a psychological test, Wikipedians, as expected, “were more comfortable online than in the real world” but they, surprisingly, scored low even on agreeableness and openness.

During an Italian conference dedicated to music on the Net, one boy asked the speaker, “We can download the complete discography of any artist, but the problem is: What do we like?” An interesting question, which gives the real point of the matter.

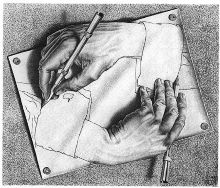

Choices are connected with our personality; choices are bridges between our inner view and an external event. We can make the right choices for ourselves only when we can listen to ourselves deep enough to access the essence of our personality and join it to the outer life. But in order to do that we need both a solid personality which we are aware of and, some quiet and empty time to look into ourselves instead of following just external inputs. Both states are quite hard to access in online life.

We tend to believe that information can construct our personality and give us an individuality. We identify ourselves mostly with what we know, with our thoughts and beliefs, in another world with what fills our mind. But those aspects are as fragile and unreal as the financial derivatives market. The ideas and beliefs which fill our minds are essentially the products of our familiar and cultural conditionings, which give the ego the illusion of being “somebody” with its unique peculiarities.

Information, detached from experience, detached from a felt inner view and detached from an ethical background, mostly reinforces our conditionings instead of opening our minds to new areas. Neil Postman, in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology (New York: Vintage Books, 1993, p. 63), wrote:

Information is dangerous when it has no place to go, when there is no theory to which it applies, no pattern in which it fits, when there is no higher purpose that it serves.

The mind’s main job and hobby is to separate, to discriminate, and to judge. It gives us a powerful way to read and act on reality which gave science and technology the strongest roles in our culture. Unless mind is subordinated to a broader (we could say spiritual) awareness, is non-inclusive by nature. In this view it is not surprising to know that online, we tend to stay in our territory with what is already known and accepted by our minds. Our social connections online can surely broaden minds too but mostly, as happens with other media, they promote uniformization.

Actually, we experience the paradox of both uniformization and the explosion of differences; Lee Siegel expressed this paradox as one “must sound more like everyone else than anyone else is able to sound like everyone else” (Against the Machine, New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2008, p. 73).

The source of this apparently contradictory phenomenon is in the ego itself, which does need to be recognized and accepted by people but at the same time feel different from anyone else in order to prove its specialness. Commercially, we are presented with millions of choices to let us think we are unique but then people tend to choose what is known or anyway what is known by somebody we want to be connected with and recognized by, much as teenagers are dependent on the peer group’s opinions.

When we are presented with millions of commercial options and we choose one we delude ourselves in thinking we are recognizing ourselves and building a part of our individuality. The market, as the Situationists had already seen in the 1950s, first takes away our real needs of connection and authenticity, then illudes us in giving what we need, but in a pale reflection of the real, making us always thirsty for a ‘real’ which will never come.

The variety expressed on the Web is well developed and important and will expand even more, but it seems that the force toward variety turned back into concentration of sources of information, as Nicholar Carr said in an interview for The Sun magazine.

It was once believed that the Web was essentially centrifugal: that it pushed people away from big, central sources of information to millions of small, independent sources scattered throughout the network. But it turns out that centripetal forces – forces that draw us back to the big power centers – are also strong on the Web. Big sites have big advantages, and they seem to get stronger over time. The Net’s Wild West days are coming to an end. The trend now is more toward the consolidation of traffic and power than toward their diffusion.

Our choices about information can come from our depth if we allow ourselves to sense our very depth. The more we swallow information the less we are able to make real choices. We can’t make real choices because we don’t listen to ourselves; and we don’t listen to ourselves because the capacity of our inner attentional muscles is never exercised and it becomes weak by attending only external inputs mostly of short bits of information with no broad view. When we can’t approach our inner self or when the very habit of looking inside becomes weakened, we can only consign our choices to the mass or perhaps just to the faster website. In this way we identity more with the contents of information poured into our minds and less with our essential qualities.

One of the mantras of the Internet is that there aren’t barriers of social status, religion, country, ideology. This is true of our possibility to access any kind of information on the Net, but the more we identity ourselves with our mind’s contents, the more we erect defenses against extraneous information which would shake our mind’s structures and therefore our very identity. The real broadening of the mind can happen when we don’t identify with our mind’s beliefs and ideas, but with our felt inner qualities which are being supported by the observation of our mind’s processes and by the acceptance of the emptiness of our mind.

Da quando Internet è entrato nelle nostre vite è stato ritenuto come il medium che avrebbe dovuto stimolare un incontro positivo tra le culture ed a facilitare la diffusione delle informazioni che venivano trascurate dai media tradizionali. Pur essendo vero che chiunque può aprire un blog o un sito web con un minimo investimento tecnico e finanziario e condividere così i propri scritti, musica o video the il mondo intero, sembra che i grandi media siano ancora più grandi in Rete e che la comprensione tra le culture non sia molto migliorata anche 15 anni dopo la diffusione di massa di Internet.

Da quando Internet è entrato nelle nostre vite è stato ritenuto come il medium che avrebbe dovuto stimolare un incontro positivo tra le culture ed a facilitare la diffusione delle informazioni che venivano trascurate dai media tradizionali. Pur essendo vero che chiunque può aprire un blog o un sito web con un minimo investimento tecnico e finanziario e condividere così i propri scritti, musica o video the il mondo intero, sembra che i grandi media siano ancora più grandi in Rete e che la comprensione tra le culture non sia molto migliorata anche 15 anni dopo la diffusione di massa di Internet.

Se osserviamo il mondo accademico, l’Economist ha pubblicato un articolo intitolato “Le grandi menti pensano (troppo) simile” dove viene presentata la ricerca di James Evans, un sociologo dell’università di Chicago, il cui lavoro è stato pubblicato su Science. Le conclusioni del suo lavoro sono che “all’aumentare delle riviste disponibili online, un numero minore di articoli vengono menzionati nell’elenco degli scritti di ricerca. Inoltre, gli articoli che vengono maggiormente menzionati tendono ad essere quelli pubblicati più di recente. Invece di crescere in lunghezza, la coda lunda viene tagliata”. La coda lunga è un termine coniato da Chris Anderson nel 2004 per definire i mercati di nicchia che possono essere approcciato dal Web, dove i prodotti unici assumono un’importante valore commerciale.

Evans ha scoperto al contrario che la grande varietà di articoli disponibili in Rete, lungi dall’espandere la portata delle fonti citate, in realtà privilegia quelle che sono già note e in maggior modo le più recenti, probabilmente le più semplici da trovate con Google.

A livello commerciale, New Scientist ha pubblicato l’articolo “Lo shopping online e l’effetto Harry Potter“, scrivendo che “i grandi venditori non sono mai stati così grandi… Andrew Bud dell’azienda di software per cellulari mBlox ha analizzato un anno di download da un famoso negozio di musica su Internet. Ha trovato che, dei 13 miioni di brani disponibili, 52.000, solo lo 0,4 percento dei titoli, produceva l’80 percento dei download.

New Scientist spiega il fenomeno così: “la facilità della copia digitale e la comunicazione efficiente tramite i cellulari, le email e i social network incoraggia le mode che si muovono e cambiano velocemente. Il risultato è una omogeneizzazione dei gusti che accrescono le probabilità che qualcosa di popolare diventi un bestseller, portando maggiore successo a ciò che lo ha già”.

Questo è stato confermato sperimentalmente da Duncan Watts, un sociologo alla alla Columbia University di New York.

Insieme con i suoi colleghi Matthew Salganik e Peter Dodd, ha testato gli effetti della comunicazione e l’approvazione dei coetanei sui gusti musicali di 14.000 adolescenti reclutati online come volontari (Science, vol. 311, p. 854). Ai volontari è stato messo a disposizione un set di 48 canzoni. I volontari avrebbero potuto scaricare qualsiasi canzone. I ricercatori hanno diviso i volontari in otto gruppi; in alcuni, i membri dei gruppi potevano vedere ciò che stavano scaricando i loro coetanei, ma in altri non vi era tale informazione. Nei gruppi socialmente connessi, il vincitore prese tutto: le canzoni popolari divennero ancora più popolari, quelle non popolari divennero ancora più trascurate. Questo effetto era meno evidente nei gruppi socialmente isolati.

Watts ritiene che il sovraccarico di informazioni ci rende più dipendenti rispetto alle opinioni altrui per capire cosa ci piace. Quindi New Scientist si chiede: “perché, quando abbiamo così tante informazioni a disposizione, siamo così preoccupati rispetto ai gusti degli altri? Non ci fidiamo dei nostri giudizi?”

In un altro articolo, uno psicologo ha scoperto che i Wikipediani sono scontrosi e chiusi di mente. In un test psicologico, i Wikipediani, come ci si sarebbe aspettato, “erano più a loro agio online che nel mondo reale” ma anche, sorprendentemente, hanno avuto un basso punteggio rispetto alla cortesia e all’apertura.

In Italia, durante una conferenza dedicata alla musica in Rete, on ragazzo ha domandato allo speaker: “Possiamo scaricare la discografia completa di qualsiasi artista, ma il problema è: Cosa ci piace?”. Una domanda interessante che dà il vero senso della questione.

Le scelte sono connesse con la nostra personalità, le scelte sono ponti tra la visione interiore e un evento esterno. Possiamo effettuare le scelte opportune per noi quando possiamo ascoltarci abbastanza in profondità in modo da accedere all’essenza della nostra personalità e collegarla alla vita esterna. Ma per poter fare questo necessitiamo sia di una solida personalità di cui siamo consapevoli e di un lasso di tempo tranquillo e vuoto per guardare al nostro interno invece di rincorrere solamente input esterni. Entrambi gli stati sono difficili da ottenere nella vita online.

Tendiamo a credere che le informazioni possano costruire la nostra personalità e darci una individualità. Ci identifichiamo primariamente con ciò che conosciamo, con i nostri pensieri e ciò a cui crediamo, in altre parole con ciò che ci riempie la mente. Ma tali aspetti sono fregili e irreali come i mercati finanziari dei derivati. Le idee e le credenze che ci riempiono la mente sono essenzialmente i prodotti dei nostri condizionamenti familiari e culturali, che danno all’ego l’illusione di essere “qualcuno” con le sue uniche peculiarità.

L’informazione, staccata dall’esperienza, separata da una visione interiore sentita e scollegata da una base etica, più che altro rinforza i nostri condizionamenti invece di aprirci la mente verso nuove aree. Neil Postman, in Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology (New York: Vintage Books, 1993, p. 63), scrisse:

L’informazione è pericolosa quando non ha un luogo dove andare, quando non c’è una teoria a cui si applica, nessun modello a cui si adatta, quando non serve uno scopo più elevato.

Il lavoro e l’hobby principale della mente è quello di separare, di discriminare, di giudicare. Ci fornisce un modo potente per leggere e agire sulla realtà, che ha dato alla scienza e alla tecnologia i ruoli predominanti nella nostra cultura. A meno che la mente non è subordinata ad una consapevolezza più estesa, essa è non-inclusiva per natura. Secondo questo punto di vista non ci si sorprende che online tendiamo a rimanere nel nostro territorio con ciò che è già conosciuto ed accettato dalla nostra mente. Le nostre connessioni sociali online possono senza dubbio ampliare le menti, ma, soprattutto, come già avviene con altri media, promuovono l’uniformità.

In reatà vediamo il paradosso dell’uniformità insieme all’esplosione delle differenze; Lee Siegel ha espresso questo paradosso in modo tale che una persona “deve sembrare di più come chiunque altro che qualsiasi altra persona sembri come chiunque altro”. (Against the Machine, New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2008, p. 73).

La fonte di questa apparente contraddizione è nell’ego stesso, che necessita di riconoscimento e di essere accettato dal prossimo, ma allo stesso tempo di sentirsi diverso da chiunque altro per poter dimostrare il suo essere speciale. Commercialmente ci vengono proposte milioni di scelte per farci credere di essere unici ma di fatto le persone tendono a scegliere ciò che è già noto oppure ciò che è noto a qualcuno a cui vogliamo essere connessi ed apprezzati, analogamente agli adolescenti che dipendono dalle opinioni dei coetanei.

Quando ci propongono milioni di opzioni commerciali e ne scegliamo uno, ci illudiamo nel credere che stiamo riconoscendo noi stessi e costruendo una parte della nostra individualità. Il mercato, come avevano già osservato i Situazionisti negli anni 50, come prima cosa ci toglie i nostri bisogni reali di connessione ed autenticità, poi ci illude nel darci ciò che necessitiamo, ma in un pallido riflesso del reale, lasciandosi sempre assetati per un “reale” che non giunge mai.

La varietà espressa dal Web è ampia e importante e si espenderà ulteriormente, ma sembra che le forze verso la varietà si sono rigirate verso la concentrazione delle fonti di informazione, come ha affermato Nicholas Carr in un’intervista per il The Sun magazine.

Una volta si credeva che il Web era essezialmente centrifugo: che spingeva le persone lontano dalle grandi fonti centrali di informazione verso limioni di fonti piccole e indipendenti frammentate nella rete. Ma risulta chele forze centrifuche – forze che ci riportano indietro verso i grossi centri di potere – sono altrettanto forti sul Web. I grandi diti hanno grandi vantaggi e sembra che diventino più forti con il passare del tempo. I tempi del Vecchio West in Rete stanno volgendo alla fine. La tendenza ora è più verso la consolidazione del traffico e del potere che verso la loro diffusione.

Le nostre scelte riguardo le informazioni possono arrivare dal nostro profondo se ci consentiamo di sentire la nostra profondità. Più ingoiamo informazioni meno siamo in grado di effettuare scelte autentiche. Non possiamo scegliere in modo autentico perché non ci ascoltiamo e non ci ascoltiamo perché non esercitiamo mai i nostri muscoli dell’attenzione interiore e di conscguenza si indeboliscono prestando attenzione solo ad input esterni e perlopiù brevi frammenti informativi senza un’ampia visione. Quando non possiamo contattare il nostro sé o quando l’abitudine di grandarsi dentro si indebolisce, possiamo solamente rimettere le nostre scelte alla massa o magari al sito web più veloce. Così facendo ci identifichiamo maggiormente con i contenuti delle informazioni che vengono versate nella nostra mente e meno con le nostre qualità essenziali.

Uno dei mantra di Internet è che non vi sono barriere di status sociale, di religione, di nazione o ideologiche. Questo è vero per quanto riguarda la possibilità di accedere qualsiasi tipo di informazione in Rete, ma più ci identifichiamo con i contenuti della mente, più edifichiamo difese contro le informazioni estranee che scuoterebbero le nostre strutture mentali e di conseguenza la nostra identità. La vera apertura mentale può avvenire quando non ci identifichiamo con le idee e le credenze della mente, ma con le nostre qualità interiori sentite che vengono supportate dall’osservazione dei processi mentali e dall’accettazione del vuoto mentale.

.jpg)