Ivo Quartiroli: Prof. Magatti, how would you define techno-nihilistic capitalism, the subject of your book, Libertà immaginaria: Le illusioni del capitalismo tecno-nichilista (Imaginary freedom: The illusions of techno-nihilistic capitalism), and what are the differences with the previous stages of capitalism?

Prof. Mauro Magatti: The idea is to give a complete picture of the last 30 years which began with the coming of so-called neo-liberalism in the Anglo-Saxon countries. My book traces and develops the hypothesis of authoritative colleagues, especially the works of Boltanski in France, Bauman in England and Beck in Germany.

The idea is that those 30 years represent something as unitarian, which is detached from the previous stages (which I call “societal capitalism”), and is based not only on the nation state, but on the social and economic effects which the nation state is not able to load and which are usually referred to as “the welfare society.” The fundamental peculiarity of techno-nihilistic capitalism is a kind of new vision of the world, a new weltenshaung, which makes nihilism, traditionally a philosophy which expresses itself in stages of decadence when the established values had to be destroyed, a useful vision for accelerating both economic and technological growth on a planetary scale.

There’s a capitalism which tries to free itself from the cultural background which the national state established. This capitalism defines itself in an alliance between a technique which is supposed to be intangible, in a very thin cultural setting, or even when it is absent and, on the other side, a full availability, a full manipulability of every cultural meaning, which has to be continuously redefined, transformed, and overcome.

Quartiroli: You affirm that technology gives an imaginary freedom, yet many people, based on this very interview, could well say the opposite. I came to know about your book on the Net, sent you an email and you graciously agreed to be interviewed by me. We use Skype for the interview and then I will publish it in my blogs. This gives us a broad freedom. We don’t have any editorial limitation regarding space or length and we don’t have a director to approve our conversation. Online, we don’t even need to publish it before a certain date. And even better, we can reach hundreds or maybe thousands of readers in every corner of the world directly.

Kevin Kelly, one of the most passionate supporters of technology, in his recent article “Expansion of Free Will” says that, “Technology wants choices. The internet, to a greater degree than any technology before it, offers choices and options.” And more, “the technium continues to expand free will as it unrolls into the future. What technology wants is more freedom, expanded free will.” The idea of freedom and expansion of our possibilities is chased by every technological gadget and by every software which interacts with us. All seems very pleasurable, free and fulfilling, so what’s wrong in this expansion of our options?

Magatti: Kelly’s quote is excellent and gets to the point. Techno-nihilistic capitalism, passing the previous stage of societal capitalism, legitimates itself through this increasing of possibilities, which then is connected to the expansion of choices.

Nobody can deny that, in general terms, to go from a condition where we have less opportunities and choices to one where, instead we have the possibility of expanding our doings, in a way expands our freedom. For instance, when we can move easily and quickly from one part of the planet to the other, we get more chances to “do.”

The point is, what happens in a world where the freedom of choices, where this increase of opportunities is being produced with the speed we experience in our personal and collective lives? We should ask ourselves whether this increase has any effect on the very freedom we want to achieve.

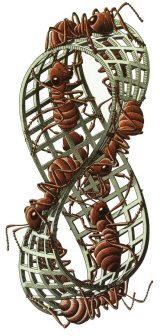

A tangible example to make the point: freedom is somehow like the eye. The eye opens to what is in front, is a sense organ somehow indeterminate since it is connected to what is being seen. The fast-increasing choices in the individual experience give us an excess of things we can see, as fundamental changes in our way of seeing, and we are even subject to the powerful systems which are there to put things in front of our eyes.

This brings the risk of becoming people who are driven from the outside: something is being presented as a choice, which is pleasurable and which increases our power and our fulfillment, but with the risk that freedom implodes on itself and that will deliver us completely to something which is external of ourselves.

To this first problem there’s a second one: all of those opportunities presented to us aren’t as real for most people as they are supposed to be. Therefore, the opportunities in front of us are kept only in an illusory and fantasized state and we withdraw them in. To give a banal example, miraculous or even magical solutions, as would be winning 130 million euro on the Lotto which would allow us to do anything we wanted to, at least in our fantasy.

Because of those two reasons, that world with expanded possibilities which is theoretically associated with an increased freedom, then carries the risk of encaging freedom again. In the book I don’t envision a world where we go back in limiting our opportunities, but to ask ourselves about our freedom and understanding if we are as free as we think we are.

Ivo Quartiroli: Prof. Magatti, come definirebbe il capitalismo tecno-nichilista, oggetto del suo libro Libertà immaginaria. Le illusioni del capitalismo tecno-nichilista (Feltrinelli. 2009) e in cosa differisce dalle fasi precedenti del capitalismo?

Mauro Magatti: Il tentativo è di dare un inquadramento unitario agli ultimi trent’anni che cominciarono con l’avvento nei paesi anglosassoni del cosiddetto neo-liberismo. Il lavoro ricalca, riprende, sviluppa tesi di colleghi autorevoli, in particolare il lavoro di Boltanski in Francia, di Bauman in Inghilterra e di Beck in Germania.

L’idea che questi trent’anni costituiscano qualcosa di unitario, che si distacca molto dal periodo precedente, che io chiamo capitalismo societario, è basato non solo sullo stato nazionale, ma sugli effetti sociali ed economici che lo stato nazionale non è in grado di determinare e che normalmente vanno riferiti all’idea della società del welfare. La caratteristica fondamentale del capitalismo tecno-nichilista è una sorta di nuova visione del mondo, di weltenshaung, che fa del nichilismo, tradizionalmente un impianto filosofico che si esprime nella fasi di decadenza quando si devono distruggere i valori che si sono stabilizzati nel corso del tempo, una visione utile per un’accelerazione della crescita sia economica che tecnologica molto rapida e su scala planetaria.

C’è un capitalismo che cerca di liberarsi dal sustrato culturale che lo stato nazionale aveva depositato. Questo capitalismo cerca invece di mostrarsi in questa alleanza tra una tecnica che come tale si propone di essere astratta, cioé con un vincolo culturale molto contenuto se non addirittura assente e d’altra parte una piena disponibilità, una piena manipolabilità di tutti i significati culturali che devono continuamente essere rimessi in gioco, superati ed essere disposti alla trasformazione.

Quartiroli: Lei afferma che la tecnica conferisce una libertà immaginaria, eppure molti, basandosi su questa stessa intervista potrebbero affermare il contrario. Ho conosciuto il suo libro in rete, le ho scritto una email, lei gentilmente mi ha concesso un’intervista, che effettuiamo tramite skype e che verrà pubblicata sui miei blog. Questo ci dà un’ampia libertà, non abbiamo le costrizioni editoriali di spazio o un direttore che debba approvare la conversazione. Non necessitiamo neanche di una data di scadenza per la pubblicazione online. Ciliegina sulla torta, possiamo raggiungere centinaia o forse migliaia di lettori in ogni parte del mondo in modo diretto.

Kevin Kelly, uno dei più convinti fautori della tecnologia, nel suo recente articolo Expansion of Free Will afferma che “La tecnologia porta alle scelte. Internet, più di qualsiasi altra tecnologia precedente, offre scelte ed opzioni.” E poi “il technium continua ad espandere la libera scelta mentre si scolge nel futuro. Ciò che la tecnologie vuole è più libertà e una libera scelta più ampia”. L’idea di libertà e di espansione delle nostre possibilità viene rincorsa da ogni gadget tecnologico e da ogni software che interagisce con noi. Sembra tutto molto piacevole, libero e soddisfacente, cos’è che non quadra quindi in questa espansione delle nostre possibilità?

Magatti: La citazione di Kelly è ottima e coglie esattamente il punto, e cioé che il capitalismo tecno-nichilista, superando in questo la fase precedente del capitalismo societario, si legittima in modo di questo suo aumento delle opportunità, che poi si lega al tema della scelta.

Indubbiamente nessuno può negare che in termini generali, passare da una situazione in cui abbiamo meno opportunità e meno possibilità di scelta ad una nella quale abbiamo invece la possibilità di fare più cose in un certo senso certamente aumenta la libertà, ad esempio potersi spostare più rapidamente da una parte all’altra del globo ci dà più possibilità di “fare”.

La questione è cosa succede in um mondo dove la libertà di scelta, questo aumento delle opportunità si produce con la velocità che constatiamo nella nostra vita personale e collettiva. Dobbiamo anche chiederci se questo aumento poi non ha conseguenze sulla libertà che vogliamo raggiungere.

Faccio un esempio concreto per capire il punto: la libertà è un po’ come l’occhio. L’occhio si apre a ciò che si pone davanti, è un organo di senso in qualche modo indeterminato e la sua indeterminatezza va messa in relazione a ciò che si vede. L’aumento così accelerato della scelta nell’esperienza individuale ci pone nella condizione di un eccesso di cose a cui possiamo guardare, come cambiamenti fondamentali nel nostro modo di guardare, ma anche addirittura soggetta a quei sistemi molto potenti che sono deputati a metterti davanti agli occhi questo e quest’altro.

Questo porta al rischio che diventiamo esseri a trazione esteriore: qualche cosa viene prospettata come scelta, gradevole e che ci aumenta la nostra potenza, la nostra realizzazione, ma con il rischio che la libertà imploda su se stessa e che ci consegni mani e piedi a qualche cosa che è fuori di sé.

A questo primo problema se ne aggiunge poi un secondo e cioé che tutte queste opportunità che ci vengono presentate, per moltissimi non sono poi così concrete come si pretenderebbe fossero. Quindi le opportunità che vengono presentate rimangono puramente illusorie, fantasticate, e ci si rifugia quindi in soluzioni, per banalizzzare il discorso, miracolistiche o addirittura magiche come potrebbe essere la vincita di 130 milioni al Superenalotto che ci consentirebbe poi di fare tutto ciò che vogliamo, almeno nella fantasia.

Almeno per queste due ragioni, quel mondo con più opportunità che viene che in linea di principio è associato certamente ad un aumento di libertà, rischia poi soprendentemente di ingabbiarla nuovamente. Nel libro il mio tentativo non è quello di immaginare un mondo in cui torniamo a limitare le opportunità ma interrogarci sulla nostra libertà e di capire se siamo così liberi come pensiamo di essere. Leggi tutto “The techno-nihilistic capitalism, interview with Mauro Magatti

Il capitalismo tecno-nichilista, intervista con Mauro Magatti“